Olmecs

These ancient Olmecs inhabitants of Mexico carved strange giant heads whose significance we are only now beginning to understand. The Olmec culture was from about 2500 to about 500 BC. Tracked along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

Their origin? Rites? Decline? We still do not know much about this civilization, the oldest of Mesoamerica, which influenced the Mayas and the Aztecs.

The Olmecs cities are the first cities of Mesoamerica, nearly a millennium before the Mayan cities (Le Mirador). Globally, the Olmecs are contemporaries of the Phoenicians. The first Olmec pyramid was built at La Venta (- 1000) at the time of the founding of the Kingdom of Israel in Palestine and two thousand years after the construction of the pyramid of Cheops in Egypt. The Olmec civilization therefore predates Greek civilization. The Panhelenic center of Delphi did not develop until the 8th century BC, and it was precisely when the Olmec civilization declined in the 6th century BC that Athens became a city-state. With the death of Socrates, the Olmec splendor passed, eclipsed by the first Mayan cities.

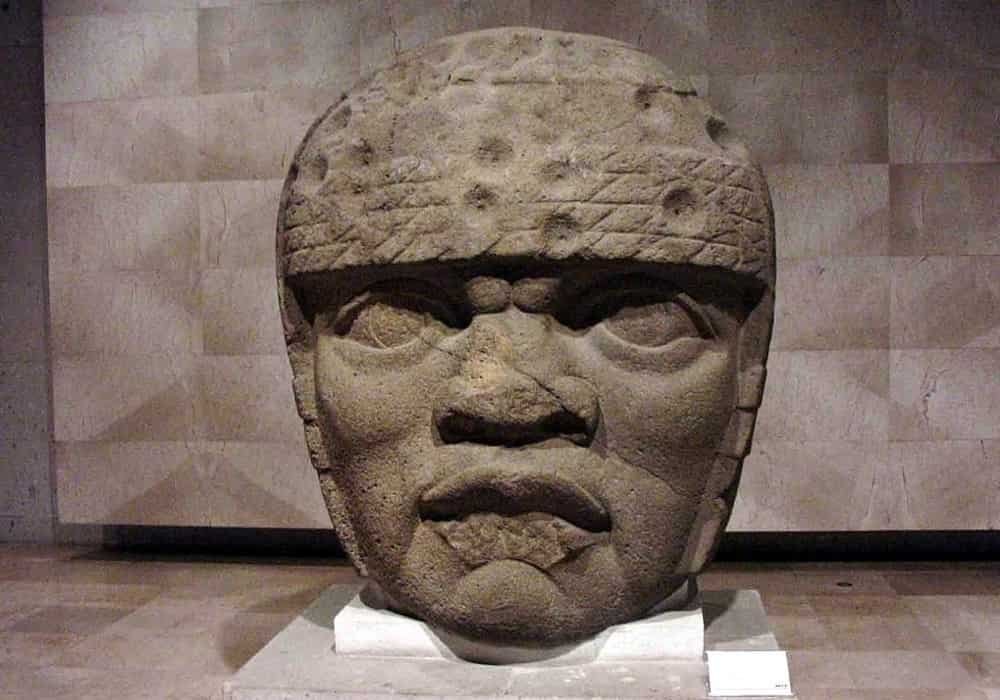

Colossal Olmec heads

The colossal Olmec heads are at least seventeen monumental stone representations of human heads carved from large basalt boulders. The heads date back to at least before 900 BC and are a defining feature of the Olmec civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. All portray mature men with fleshy cheeks, flat noses and slightly crossed eyes; their physical characteristics correspond to a type that is still common among the inhabitants of Tabasco and Veracruz . The backs of monuments are often flat.

The boulders were brought from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountainsof Veracruz. Since the extremely large stone slabs used in their production were transported over long distances, requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, the monuments are thought to represent portraits of single, powerful Olmec rulers. Each of the known specimens has a distinctive headdress.

The heads were variously arranged in rows or groups at major Olmec centers, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to these sites remain obscure. The discovery of a colossal head at Tres Zapotes in the 19th century spurred the first archaeological investigations of Olmec culture by Matthew Stirling in 1938. Seventeen confirmed specimens are known from four sites within the Olmec nuclear area on the Gulf coast of Mexico . Most of the colossal heads were carved from spherical boulders, but two from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were re-sculpted from two massive stone thrones. Another monument, to Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, is a throne that may have been carved out of a colossal head. This is the only known specimen from outside the Olmec area.

Hypotheses

Besides a small number of proven elements, as often in olmecology, a large part of the literature on colossal heads consists of hypotheses, about which the consensus is more or less great. The body of colossal heads is extremely small: exactly seventeen. We can therefore legitimately wonder whether it is a representative sample of this type of monument, which calls for the greatest caution.

The meaning of colossal heads is not known. Currently, the most common assumption is that they are portraits, probably of Olmec rulers. The remarkable individuality of each head, be it facial features or cuff, argues in favor of this theory.

According to another hypothesis, the heads represent ball players, which their hairstyle could possibly suggest. The ball game is a pervasive phenomenon in Mesoamerica. It has even been thought that they are beheaded ball players; the head of La Cobata, whose eyes seem closed, is at the origin of this hypothesis that Caterina Magni however convincingly refutes.

Two of San Lorenzo’s heads were undoubtedly recycled from altars / thrones. It is possible that this is the case with many heads, which includes heads in the phenomenon of “mutilation” of Olmec monuments. A very widespread hypothesis explains it by an invasion or a revolution. The mutilated thrones would be monuments in the process of being recycled into colossal heads. The recent discovery of a recycling workshop in San Lorenzo goes in this direction.

It is also unknown whether the heads are carved during the individual’s lifetime or after death. Three of the heads of La Venta formed a row, north of Complex C, which appears to be the “funerary” part of the site. David C. Grove thinks they are portraits of “ancestors”, although in San Lorenzo the archaeological context is less clear than in La Venta.

At the end of the 19th century, José Melgar y Serrano described the appearance of the first colossal head as “Ethiopian”. Speculations on an African origin of the Olmecs resurfaced in 1960 in the works of Alfonso Medellín Zenil and in the 1970s with the writings of Ivan Van Sertima. These speculations are not taken seriously by historians like Richard Diehl or Ann Cyphers.

Town planning and architecture

From Mexico to Costa Rica, this nation of builders built the first ceremonial centers in Mesoamerica, showing a very marked concern for planning. The buildings are arranged on a north-south axis, a general orientation that will become an urban planning convention. Monumental art – altars, steles, various roundabouts… – punctuates cities for the first time and enhances the prestige of dignitaries. The desire for scheduling is evident right up to the location of the dedicatory deposits, which are intentionally buried. The sense of space is open as evidenced by the marked taste for esplanades, squares and ample perspectives.

The Olmec workers did not hesitate to develop the land and modify the topography of the sites as in San Lorenzo, in the south of Veracruz, in the middle of the coastal swamps. Indeed, this ancient site, located on the banks of the Rio Coatzacoalcos, is an artificial plateau, entirely built by human hands. In general, there is a desire to adapt architecture to the natural environment.

Read also: Chernobyl (Ukraine) History and Disaster of Nuclear Contamination

At the architectural level, the key buildings are in place. From that time on, the pyramid was already the main building of the religious center. In La Venta, it rises in a marshy area. Its conical shape carved out of furrows recalls the morphology of a volcano, probably one of the cones of the Los Tuxtlas massif, about a hundred kilometers away.

The first ball courts appear. A very representative example is the land of Abaj Takalik (also called Takalik Abaj) in Guatemala, made up of three low clay structures and whose central alley is 23 meters long and 5.60 meters wide. The whole is oriented north-south. We should also note the construction of steam baths, corbelled vaults, megalithic tombs and ritual enclosures as in Tlacozotitlan in Guerrero. Comparable to the sites on the Gulf coast, due to its scale and imposing architecture, Tlacozotitlan offers a rectangular enclosure made up of cut stones, punctuated by four monoliths bearing the effigy of the “were-jaguar”, a hybrid creature halfway through. human and half-feline.

Another remarkable architectural element is the drainage system. While many Olmec sites have a canal system, that of San Lorenzo, unearthed in the 1960s during the Yale University excavation campaign, is certainly the most complete. This vast irrigation system was made up of basalt canals. The stones well cut and joined to each other formed, with the various reservoirs and basins dug in different places, a very advanced system of water control making it possible to have pure water. Works of art punctuated it such as monument 52 with the effigy of a were-jaguar, located near one end of the aqueduct or a basin in the shape of a palmiped bird, monument 9 of the site.

In all the Olmec cities, the use of beaten earth, clay and stone as building materials is widely documented.

Sociopolitical organization

Little is known about Olmec society, which perhaps explains the differences of opinion. Opinions that agree on only one point: the existence of a crucial period between 1000 and 900 BC, marked by important changes attributable to several factors. Among them, let us mention the introduction of new agricultural techniques allowing a better diet and consequently a demographic growth, the intensification of the commercial exchanges, an important urbanization accompanied by a strong social stratification, a centralization of the political powers, a institutionalized religion and, in general, a specialization of activities.

During this period, there is an intensification of architectural and sculpture work. Stone monuments punctuate the ceremonial centers and accentuate their majesty. Should we already speak in terms of the state or, more cautiously, of the transition from a segmentary clan-type society to a state society? The debate remains open.

Note the appearance of writing and the calendar. In fact, the ideo-pictographic writing is inscribed in the first place on terracotta. It was in force as early as 1200 BC over a large part of Mesoamerica and was to develop in later cultures by taking extremely elaborate forms.

Religion of Olmecs

If the nature and number of Olmecs “deities” are still the subject of controversy, it is nevertheless difficult to refute the repetitive presence of the mythical figure of the jaguar, whether he is anthropomorphized or not. The beast obviously plays a preponderant role in religious thought. This large, feared and revered predator is commonly associated with rain and agriculture. Its power is ambivalent -branched two opposites (such as loving and hating at the same time towards the same person): creator and destroyer at the same time.

Mother Earth, as a feminine principle, is also ubiquitous in the Olmec religion. Like the beast, its power is twofold. It can just as easily give life – men, plants, etc. – as it can withdraw it by engulfing living beings forever.

Art: materials and techniques

Olmec artists also distinguished themselves in the work of clay, stone and wood. In addition, the rare cave paintings unearthed show the heterogeneity of their production. A schematic approach to artistic creation leads to the distinction between monumental art and minor art.

The first includes any large-scale work whether it is carved in the round, in top and bas-relief, engraved or painted. Colossal heads, statues, altars, steles, slabs, petroglyphs, mosaics (which are called massive offerings) and wall paintings participate in this category. Among the favorite materials of colossal art, let us point out basalt and andesite, very resistant volcanic stones.

The second gathers all the small objects in stone and terracotta worked in volume, in top and bas-relief, or finely incised / excised such as figurines, axes, masks, pendants, jewelry, containers…

Some of the most popular materials for movable art include jade-jadeite, serpentine and obsidian (igneous rock occurring as a natural glass formed by the rapid cooling of viscous lava from volcanoes).

Thematic range

In the iconographic field, the human figure constitutes the main theme of Olmec art. Then, we meet the hybrid figure and, in third position, the animal subject.

The anthropomorphic figure is very rarely feminine. In fact, the image of women is mostly present in metaphorical form. It crystallizes in the image of the cave and the earthly rift. Male figures, at least those that are unequivocally recognizable, are also in reduced number. There remain the asexual figures, the majority, who seem to respond to aesthetic or ideological conventions. Despite the absence of the indication of the sex, their overall morphology, even the wearing of a loincloth and the presence of a goatee, demonstrate that it is indeed the representation of a man.

The hybrid figure is recurrent. The Olmec artist represents various degrees of the human-animal relationship, but only paints a complete and exhaustive picture with the figure of the jaguar. This is how he depicts situations that can be qualified as “extreme” – alliance / kinship and antagonism – and “intermediaries” – hybridization, metamorphosis… These artistic manifestations suggest a systematic exploration of the human relationship. -jaguar and its reciprocal. From this perspective, the image of the were-jaguar, where anthropomorphic and zoomorphic features cleverly intermingle, is a perfect example.

In an art imbued with animality, it is surprising to note the rarity of animal effigies. In this category, the place of honor once again goes to the feline. Then, further on, to other large predators such as the snake, especially the rattlesnake, and the eagle. Herbivores – deer and other small mammals – are in the minority.

In fact, the artist’s attention is primarily focused on predators, located at the top of the food pyramid, and conversely decreases with regard to prey.

Olmecs heritage

As we will have understood, if we want to understand all the complexity of Mesoamerica, we must necessarily refer to the Olmecs. Indeed, all the later cultures will drink in this first matrix.

The heritage is also palpable in many areas, whether material or intellectual.

In town planning, Olmec ceremonial centers, such as La Venta, foreshadow later cities. Moreover, there are all the architectural creations characteristic of Mesoamerica: pyramids, ball playgrounds, drainage systems, tombs, ritual spaces and vast esplanades …

The pyramid, in particular, will become one of the architectural constants of Middle America.

From Epoch II, the builders of Monte Alban (Oaxaca) and Teotihuacan (high central plateau of Mexico) show the same concern for rigor in the planning, general orientation and arrangement of buildings as that of their predecessors.

The use of flanking a pyramidal structure of sculpted monoliths, the use of the column as an architectural element, the false vault, the steam bath… are all features that are hastily attributed to late civilizations and which, in fact, belong to the Olmecs.

In the artistic field, later cultures continue to chisel jade, with green and bluish hues, and to carve large blocks of stone.

Altars, steles, roundabouts… punctuate the cities. The cult of the “governor”, mentioned above, is repeated later. To be convinced of this, just think of the Mayan stelae which depict the “king in majesty”, full-length, richly dressed, scepter in hand.

In the intellectual field, it was the Olmecs who invented writing, of an ideopictographic nature, and the calendar. The so famous Mayan script has its roots in this first glyphic system.

The influence is also felt in the religious field. Generally speaking, zoolatry, the cult of ancestors, children and deformed beings… persisted over the centuries. At the same time, ritual practices, such as burning incense or rubber as an offering, and socio-aesthetic practices such as dental mutilation or cranial deformation, spread. As for sacrificial practices, they undoubtedly date back to the Olmec horizon.

Finally, a large number of late “deities” are dependent on the Epoch I jaguar.

Of course, parentage is sensitive to varying degrees. So while Tlaloc, the Mexican rain god, clearly perpetuates the feline characters, Quetzalcoatl, the famous “Feathered Serpent”, hides them from the unfamiliar eye.

These fundamental traits that the first great civilization of Mexico bequeathed to late cultures have been found throughout the centuries. The cultural and historical continuity of Mesoamerica is, without a doubt, exceptional.

The End of the Olmecs Civilization | Why did the ancient Olmec civilization disappear?

Sources: PinterPandai, Khan Academy, National Geographic