Glycogen Storage Disease

Glycogen storage disease prevents the human body from properly processing its stores of sugar, stored in the liver as glycogen. This causes an enlarged liver, muscle weakness and abnormally low blood sugar levels.

Glycogen is a form of glucose (sugar), a main source of energy that your body stores primarily in your liver and muscle, for future energy needs.

There are many types and named, all of which are caused by deficiencies of the enzymes involved in glycogen synthesis or breakdown; these deficiencies may exist in the liver or muscle and cause hypoglycemia or the deposition of abnormal amounts or types of glycogen (or its intermediate metabolites) in the tissues.

There are several types of muscle glycogenosis:

- Muscle glycogen synthase deficiency (glycogen storage disease type 0)

- Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II)

- Cori’s disease or Forbes’ disease (glycogen storage type III)

- Andersen’s disease (glycogen storage type IV)

- Mc Ardle’s disease (glycogen storage type V)

- Tarui disease (glycogen storage type VII)

- Phosphorylase kinase deficiency (glycogen storage disease type IX)

- Di Mauro disease (glycogen storage type X)

- Muscle beta-enolase deficiency (glycogen storage disease type XIII)

- Phosphoglucomutase deficiency (glycogen storage disease type XIV)

- Glycogenin-1 deficiency (glycogen storage disease type XV)

How is glycogen formed?

Glycogen is formed from dietary carbohydrates. Once ingested, carbohydrates (pasta starch, fruit sugar, etc.) are digested by the stomach, which reduces them to small glucose molecules. The organism uses some of the molecules for its functioning. The liver and muscles then store what is not used in the form of glycogen.

When needed, especially during physical exercise, the body breaks down glycogen to quickly provide energy to the muscles. Consequently, the use of these reserves is limited in time and is accompanied by the use of lipids during a long-term effort.

To summarize: Dietary carbohydrates > (Digestion) > Glucose > (Glycogenogenesis) > Glycogen > (Glycogenolysis) > Glucose

What symptoms and what consequences ?

These hepatic glycogenoses have in common the appearance of hypoglycaemia. The symptoms of hypoglycaemia are sometimes severe discomfort, with pallor, sweating and sometimes convulsions. The liver is large (except in glycogen storage disease type 0) since it is overloaded with glycogen, giving the abdomen a bloated appearance.

Hypoglycaemia occurs for a short fast of a few hours (sometimes they appear systematically less than two hours after a meal), which is why the disease may not be apparent during the first weeks of life, since it is normal for an infant to eat at regular intervals and wake up at night to eat.

Apart from hypoglycaemia, the other symptoms that may appear depend on the type of glycogen storage disease and the age of the child:

– for type Ia glycogen storage disease, excess glycogen in the liver can, from adolescence, favor the appearance of hepatic adenomas (benign tumors of the liver), which must be monitored regularly. Indeed, these adenomas can bleed and, rarely, turn into cancer. Glycogen overload in the kidneys increases their size, can impair their function and, rarely, can cause kidney failure. There is also a tendency to bleeding which is not bothersome on a daily basis, most often a few minor nosebleeds. However, if surgery is planned, specific treatment should be given to prevent heavy bleeding. Finally, osteoporosis can appear early.

– People with glycogen storage disease type Ib have, in addition to the symptoms of glycogen storage disease type Ia, impaired immunity responsible for low levels of white blood cells (neutropenia) and intestinal damage of inflammatory origin leading to canker sores, abdominal pain and diarrhea.

– for type III glycogenosis: in addition to liver damage responsible for less severe hypoglycaemia than in type I (and rarely cirrhosis in adulthood), people have muscle damage which results in fatigue on exertion and, sometimes, heart damage.

– For type IV glycogenosis: in the absence of an enzyme making it possible to make connections to glycogen, the latter does not have a normal structure and is recognized as “foreign” by the immune system. The activation of immunity leads to the progressive destruction of the liver causing cirrhosis. There is no hypoglycemia in this type of glycogen storage disease. Symptoms are mainly those of liver failure related to cirrhosis. Glycogen storage disease type IV will not be discussed further in this chapter.

– For type VI and IX glycogenosis: the main symptom is the large liver. Hypoglycaemia is rare, mild, and often inapparent.

Types of Glycogen Storage Disease

| Type (Eponym) | Enzyme deficiency (Gene) | Hypoglycemia? (low blood sugar) | Hepatomegaly? (enlarged liver) | Hyperlipidemia? elevated levels of any or all lipids (fats, cholesterol, triglycerides) in blood | Muscle symptoms | Development/ prognosis | Other symptoms |

| GSD 0 | Glycogen synthase (GYS2) | Yes | No | No | Occasional muscle cramping | Growth failure in some cases | |

| GSD I (von Gierke’s disease) | Glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC / SLC37A4) | Yes | Yes | Yes | None | Growth failure (indicates insufficient weight gain or absence of appropriate physical growth in children) | Lactic acidosis, hyperuricemia |

| GSD 2 (Pompe disease) | Acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) | No | Yes | No | Muscle weakness (including muscular dystrophy and inflammatory myopathy) | Progressive proximal skeletal muscle weakness with varied timeline (early childhood to adulthood) | Heart failure (infantile), respiratory difficulty (due to muscle weakness) |

| GSD 3 (Cori’s disease or Forbes’ disease) | Glycogen debranching enzyme (AGL) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Myopathy (disease of the muscle fibers do not function properly. Resulting muscular weakness) | ||

| GSD 4 (Andersen disease) | Glycogen branching enzyme (GBE1) | No | Yes, also liver cirrhosis | No | Myopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy | Failure to thrive (also known as weight faltering or faltering growth, indicates insufficient weight gain or absence of appropriate physical growth in children), death at age ~5 years | |

| GSD 5 (McArdle disease) | Muscle glycogen phosphorylase (PYGM) | No | No | No | Exercise-induced cramps, Rhabdomyolysis (damaged skeletal muscle breaks down rapidly. It may include muscle pains, weakness, vomiting, & confusion.) | Renal failure by myoglobinuria, second wind phenomenon | |

| GSD 6 (Hers’ disease) | Liver glycogen phosphorylase (PYGL)Muscle phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM2) | Yes | Yes | Yes | None | Initially benign, developmental delay follows. | |

| GSD 7 (Tarui’s disease) | Muscle phosphofructokinase (PFKM) | No | No | No | Exercise-induced muscle cramps and weakness | Developmental delay (in the physical, mental or emotional development of children) | In some haemolytic anaemia |

| GSD 9 | Phosphorylase kinase (PHKA2 / PHKB / PHKG2 / PHKA1) | Yes | Yes | Yes | None | Delayed motor development (e.g., catching objects, using cutlery, handwriting, riding a bike, swimming). Developmental delay (multiple basic functions including socialization & communication). | |

| GSD10 | Phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM2) | ? | ? | ? | Exercise-induced muscle cramps and weakness | Myoglobinuria | |

| GSD11 | Muscle lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA) | ? | ? | ? | |||

| Fanconi-Bickel syndrome formerly GSD 11, no longer considered a GSD | Glucose transporter (GLUT2) | Yes | Yes | No | None | ||

| GSD12 (Aldolase A deficiency) | Aldolase A (ALDOA) | No | In some | No | Exercise intolerance, cramps. In some Rhabdomyolysis. | Hemolytic anemia and other symptoms | |

| GSD 13 | β-enolase (ENO3) | No | ? | No | Exercise intolerance, cramps | Increasing intensity of myalgias over decades | Serum CK: Episodic elevations; Reduced with rest |

| GSD 15 | Glycogenin-1 (GYG1) | No | No | No | Muscle atropy | Slowly progressive weakness over decades | None |

Remarks:

- Some GSDs have different forms, e.g. infantile, juvenile, adult (late-onset).

- Some GSDs have different subtypes, e.g. GSD1a / GSD1b, GSD9A1 / GSD9A2 / GSD9B / GSD9C / GSD9D.

- GSD type 0: Although glycogen synthase deficiency does not result in storage of extra glycogen in the liver, it is often classified with the GSDs as type 0 because it is another defect of glycogen storage and can cause similar problems.

- GSD type VIII (GSD 8): In the past it was considered a distinct condition, however it is now classified with GSD type VI or GSD IXa1; it has been described as X-linked recessive inherited.

- GSD type XI (GSD 11): Fanconi-Bickel syndrome, hepatorenal glycogenosis with renal Fanconi syndrome, no longer considered a glycogen storage disease.

- GSD type XIV (GSD 14): Now classed as Congenital disorder of glycosylation type 1 (CDG1T), affects the phosphoglucomutase enzyme (gene PGM1).

- Lafora disease is considered a complex neurodegenerative disease and also a glycogen metabolism disorder.

Treatments

The treatment of children with type I glycogen storage disease is restrictive and requires, during the first years of life, the active participation of parents several times a day. This treatment has several aspects:

– prevention of fasting,

– a special carbohydrate-enriched diet,

– the treatment of associated anomalies

– monitoring of the disease and its possible complications.

1- The prevention of fasting

The number and rhythm of meals will be adapted to the child’s fasting tolerance. It thus includes essential carbohydrate intake at fixed times, including at night. No power delay is allowed.

In order to extend the duration of fasting possible during the day, after the age of 12 months, corn starch (“Maïzena®”) is given at the end of the meal, or even between meals, in order to constitute an intestinal reserve. of glucose that will pass into the bloodstream for a prolonged period. Corn starch, to retain this property, must be given raw, unheated, usually mixed with water. It can be difficult to digest (risk of diarrhoea, abdominal pain) if the child takes too large quantities.

With age, meals can be spaced out gradually according to a rhythm specific to each child and hypoglycemic accidents begin to become rarer after the age of 5 years.

At night, frequent meals are also necessary, but difficult to implement after the first weeks of life. This is why “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) is performed at night. Using a nasogastric tube or a gastrostomy tube, a tube called a “tube” is inserted into the stomach. The “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) works on the principle of an infusion, except that the liquid food preparation is administered into the stomach. The “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) aims to provide glucose (or Maltodextrin) dissolved in water continuously at night, in order to avoid hypoglycaemia. From the age of 4-5 years, the child is often able to set up his tube alone in the evening at bedtime and remove it the next morning. On the other hand, the preparation of the mixture to be administered, the adjustment of the nutrition pump and the monitoring of its operation must be done by the parents, following the medical prescription.

2- A special diet

A specialized dietitian must be involved in the management. Typically, carbohydrates provide 60 to 65% (see 70%) of energy. They are divided between slow sugars (starches), present at all meals, and fast sugars in limited quantities. In fact, in order to limit the overload of cells with glycogen, the child must have a diet controlled in other sugars, in particular galactose and lactose for type I glycogenosis (sugars contained in milk and dairy products) , since they participate in the formation of glycogen without participating in the maintenance of glycemia. Galactose and lactose intake will be limited to 10 g per day on average during the first years of life: children can thus eat sugar-free yoghurt and cheese in moderate quantities. Fructose (sugar contained in fruit) and sucrose (table, cane or beet sugar) intakes will also be limited for type I and III glycogenosis. Children can eat 1 to 2 fruits per day. Many calories being provided by carbohydrates, the share of lipids is reduced. This type of diet can induce deficiencies in vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids.

In some children, this rigor around food, in particular the close timing of food intake, can promote anorexia: the child refuses to eat by mouth. The food is then brought exclusively by the nasogastric tube or the gastrostomy tube

3- Treatment of associated anomalies

Children with type I glycogen storage disease may present with associated abnormalities which, if significant, may warrant additional oral treatment: lactic acidosis (treated by adjusting carbohydrate or even bicarbonate intake), hyperuricaemia ( treated with allopurinol) and hypertriglyceridaemia.

For people with muscle damage related to glycogen storage disease type III, walking can be made safer with a cane.

4- Monitoring the disease and its possible complications

On a daily basis, parents monitor their child’s capillary blood sugar, with a device identical to that of diabetic children. In case of hypoglycaemia, he administers glucose to their child.

Children with type I and type III glycogen storage disease are hospitalized regularly, several times a year over 2 to 3 days, in order to check blood sugar levels, re-evaluate their tolerance to fasting and readjust the treatment. In fact, after a few years, tolerance to fasting improves and it is possible to lighten the treatment. In adolescence, children usually no longer have “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) and can last nearly 6 hours without eating. The monitoring will also be attentive by blood tests in order to avoid any deficiencies that could cause the particular diet.

Emergency hospitalizations are often necessary, particularly during early childhood, due to hypoglycaemia and/or major lactic acidosis, or even due to situations where the child eats less or no food at all (vomiting, diarrhea from a mild infectious cause, etc.). A 24-hour infusion and/or “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) is then necessary in hospital.

When to be careful?

The risk of hypoglycaemia is low when the diet is well followed and meal times scrupulously respected. The student should NEVER fast.

In the event of intense sports practice, it is advisable to ensure that the student has planned to increase his carbohydrate intake.

If the student exhibits vomiting, the parents should be notified immediately and the student’s emergency kit should be taken out in order to monitor blood glucose levels and bring sugar to the child. They will in turn contact the student’s referring specialist doctor to decide what action to take.

Symptoms of hypoglycaemia are paleness with sweating and, sometimes, various consciousness and/or neurological disturbances (hallucinations, seizures, unusual behavior, etc.). These symptoms justify the realization of a capillary glycemia whose result will be transmitted to the parents and, in the event of hypoglycemia, to a contribution of glucose.

Any loss of consciousness is, until proven otherwise, hypoglycaemia. This justifies attempting a gentle sugaring of the child with a 30% glucose solution, calling the parents and the Samu.

The student may participate in school outings. The emergency kit must be carried along with the protocol to follow in the event of hypoglycaemia. It is often essential that one of the parents accompanies his child. In the case of a transplanted class, the presence of one of the parents is also essential, both to ensure that the pupil’s meal times are respected, to ensure and supervise the “enteral nutrition” (tube feeding) at night, but also, in the kitchen, to adapt the student diet menu.

Information: Cleverly Smart is not a substitute for a doctor. Always consult a doctor to treat your health condition.

Sources: PinterPandai, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, NORD – National Organization for Rare Disorders, Medscape, Duke University Health System

Photo credit: Mikael Häggström. Häggström, Mikael (2014). “Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.008. ISSN 2002-4436. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

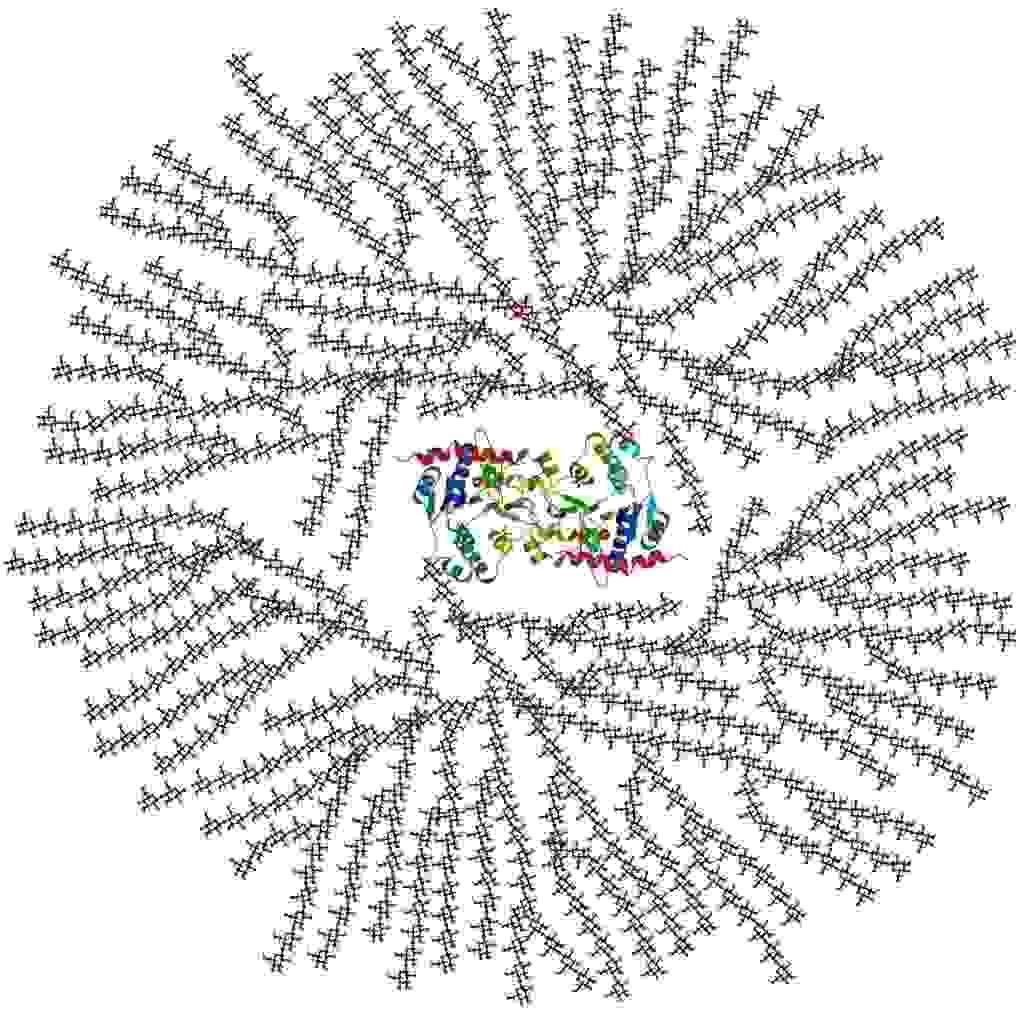

Photo description: cross-sectional view of glycogen in 2-D figure: Glycogenin core protein surrounded by branched glucose units. The entire globular complex may contain about 30,000 glucose units.

(Description reference: Page 12 in: Exercise physiology: energy, nutrition, and human performance By William D. McArdle, Frank I. Katch, Victor L. Katch Edition: 6, illustrated Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006 ISBN 0781749905, 9780781749909, 1068 pages)