What is bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer starts in the cells of the bladder. Cancerous (malignant) tumor is a group of cancer cells that can invade and destroy nearby tissue. The tumor can also spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

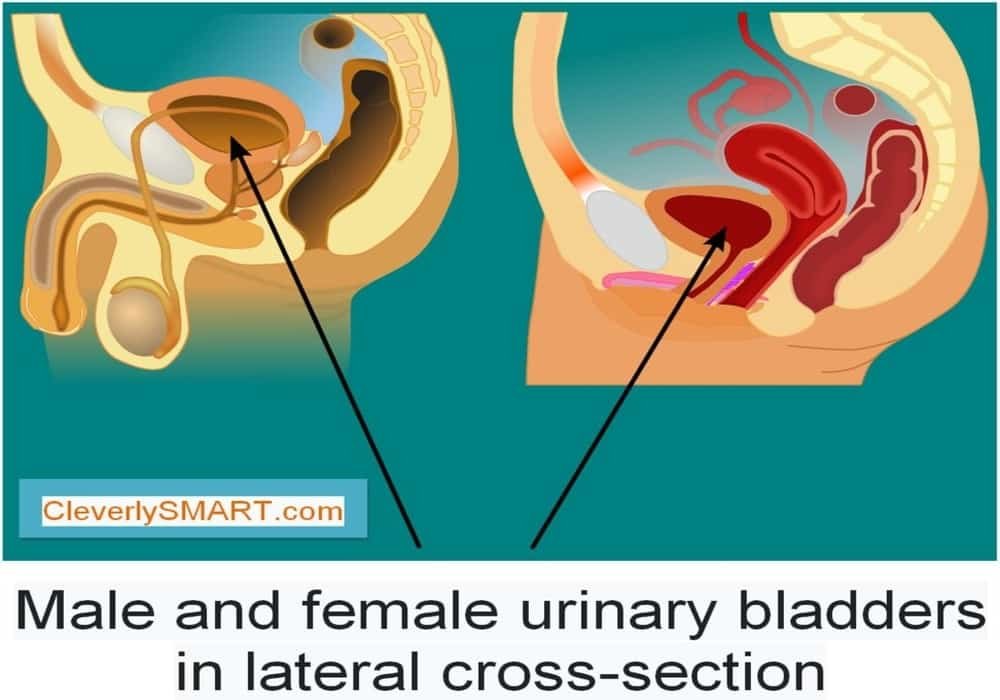

The bladder is part of the urinary tract. It is a hollow organ in the pelvis that is used to store urine (liquid waste) before it is released from the body.

Sometimes bladder cells undergo changes that make the way they grow or behave abnormally. These changes can lead to the formation of non-cancerous (benign) tumors such as papillomas. They can also cause the development of non-cancerous conditions such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), commonly called urinary tract infections.

But in some cases, changes in bladder cells can cause bladder cancer. Most of the time, bladder cancer starts in the urothelial cells that line the inside of the bladder. This type of cancer is called urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, or transitional carcinoma of the bladder.

Urothelial carcinomas account for over 90% of all bladder cancers. They are often diagnosed at an early stage and have not invaded the deeper muscle layer of the bladder wall.

Rare types of bladder cancer can also occur. Examples are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Cancerous tumors of the bladder

Cancerous bladder tumor can invade and destroy nearby tissue. It can also spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. Cancerous tumor is also called a malignant tumor.

Bladder cancer is often divided into 3 groups based on its extent (invasion) in the bladder wall.

Non-invasive bladder cancer is found only in the inner lining of the bladder (urothelium).

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer has invaded only the connective tissue layer (lamina propria).

Muscularly invasive bladder cancer has invaded the muscles deep in the bladder wall (muscularis) and sometimes the fat surrounding the bladder.

Urothelial carcinoma

Urothelial carcinoma, also called transitional carcinoma, is the most common type of bladder cancer, accounting for over 90% of all bladder cancers. It starts in the urothelial cells lining the inside of the bladder, which form a lining called the urothelium.

Urothelial carcinoma can be seen in more than one area of the urinary tract (multifocal cancer). So if the doctor makes a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma, he will check other parts of the urinary tract to see if cancer is not there, including the kidney pelvis, ureters and urethra.

Non-invasive urothelial carcinoma

Non-invasive urothelial carcinoma can be described as papillary or flat (sessile) depending on how it grows.

Papillary urothelial carcinoma looks like little fingers and often spreads towards the center of the bladder, called the lumen. Non-invasive papillary urothelial carcinoma can be high-grade or low-grade. The term low carcinogenic papillary urothelial neoplasm is used to describe a tumor that is unlikely to develop into invasive bladder cancer.

Flat urothelial carcinoma is a flat tumor that appears on the lining of the bladder. This carcinoma is high grade and more likely to extend deep into the layers of the bladder wall. Non-invasive flat urothelial carcinoma is more commonly known as carcinoma in situ (CIS).

Invasive urothelial carcinoma

Invasive urothelial carcinoma spreads beyond the inner lining, into the deeper layers of the bladder wall.

Sometimes invasive urothelial carcinoma is made up of different types of cells mixed with the usual urothelial cancer cells, called divergent differentiation. When it does, bladder cancer usually grows and spreads quickly (it is aggressive) and is more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage. Squamous cells, glandular cells and small cells are most commonly found mixed with urothelial cancer cells.

There are rare subtypes of urothelial carcinoma called variants. In general, these subtypes grow and spread quickly and tend to have a poorer prognosis than usual urothelial carcinoma. The variants of urothelial carcinoma are named after the appearance of cancer cells seen under a microscope and include the following:

- nest type

- microcystic

- micropapillary

- lymphoepithelioma type

- plasmacytoid

- sarcomatoid

- giant cell

- little differentiated

- rich in lipids

- clear cell

- Rare cancerous tumors of the bladder

The following cancerous bladder tumors are rare and represent less than 10% of all bladder cancers.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder occurs when flat squamous cells form in the lining of the bladder. It is often associated with long-term (chronic) inflammation or irritation of the bladder which can be caused by the constant insertion of a catheter (tube) into this organ over a long period, urinary stones or bladder stones. urinary tract infections (UTIs), or simply urinary tract infections, chronic.

Squamous cell carcinoma is usually invasive and diagnosed at an advanced stage. It is usually treated with surgery and sometimes with chemotherapy.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the bladder starts in the glandular cells of the bladder. It accounts for less than 2% of all bladder cancers. Adenocarcinoma can spread from the bladder to another location, called secondary adenocarcinoma of the bladder. This is why doctors need to know where the adenocarcinoma originated in order to make the diagnosis.

There are many subtypes of adenocarcinoma of the bladder including mucinous adenocarcinoma, ring cell adenocarcinoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma of the bladder is usually treated with surgery. We do a radical cystectomy to remove the entire bladder. Adenocarcinoma tends to come back, so chemotherapy is also used to treat it.

Uraque cancer

The uracha, also called the urachal ligament, is a link between the navel (umbilicus) and the bladder that forms during fetal development. In adults, there is only a thin ligament that has no function. A tumor may appear along the urachus and may turn cancerous. Urachal cancer usually starts where the urachis connects to the top of the bladder.

Urakis cancer is usually treated with surgery to remove the bladder, urachis, nearby lymph nodes, and other surrounding tissue. Chemotherapy may be given after surgery.

Small cell carcinoma

Small cell carcinoma (small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma) is a type of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) that begins in cells of the neuroendocrine system. Neuroendocrine cells are found in almost every organ in the body. Small cell carcinoma is usually a high-grade bladder cancer that grows and spreads quickly. Some people with urothelial carcinoma can also have small cell carcinoma.

Treatment for small cell carcinoma of the bladder usually includes chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove the entire bladder. Radiotherapy can also be used.

Soft tissue sarcoma

Cancer can start in the soft tissues of the bladder, such as muscle, blood vessels, or fat. This is called soft tissue sarcoma of the bladder or sarcoma of the bladder. Many people who are first diagnosed with soft tissue sarcoma actually have sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma.

The main risk factor for soft tissue sarcoma of the bladder is getting radiation therapy for another type of cancer 20 to 30 years ago.

Leiomyosarcoma (in adults) and rhabdomyosarcoma (in children) are the most common types of soft tissue sarcoma of the bladder.

Tumors and non-cancerous conditions of the bladder

A non-cancerous (benign) bladder tumor is a lump that starts in the lining or other tissue of the bladder. Non-cancerous bladder disease is a change in the cells of the bladder. Tumors and non-cancerous conditions do not spread to other parts of the body (no metastases). They are not cancers and they are usually not life threatening.

There are many types of tumors and non-cancerous conditions of the bladder.

Non-cancerous tumors

Most non-cancerous bladder tumors are rare. They can be the cause of blood in the urine and bladder problems. Cystoscopy is often used to diagnose these tumors, which could be removed during this procedure.

Papilloma starts in urothelial cells that form the inner lining of the bladder. This tumor grows away from the lining, towards the center of the bladder. Usually, there is only one small papilloma.

Inverted papilloma is usually a flat tumor that starts in the inner lining of the bladder. It invades the wall of the bladder.

The following are other rare types of non-cancerous bladder tumors:

- leiomyoma – starts in the smooth (involuntary) muscles of the bladder and is made up of an overgrowth of muscle cells

- solitary fibrous tumor – it starts in the fibrous connective tissue of the bladder wall

- hemangioma – the abnormal collection of blood vessels in the bladder

- neurofibroma – a small mass that has formed in the nerves of the bladder

- lipoma – it starts in the fat around the bladder

Non-cancerous conditions

The non-cancerous condition can affect the bladder and cause symptoms similar to those of bladder cancer.

Urinary tract infection (UTI), better known as urinary tract infection, is a common, non-cancerous condition of the bladder. UTIs are usually caused by bacteria found in the bladder and urethra. The signs and symptoms may be:

- fever, chills and malaise

- blood in the urine (hematuria)

- burning or pain when urinating

- need to urinate often (frequent urination)

- urgent need to urinate (urgent urination)

- weaker urine stream than usual

UTI is usually diagnosed by doing a physical exam and urine tests. It is usually treated with antibiotics to fight bacteria. It is also possible to take medicine to treat fever or pain.

Urinary stones, also called urolithiasis or kidney stones, are hard deposits of minerals (especially calcium) that form in the kidney. They can grow larger and extend into a ureter or bladder. Stones can cause pain (sometimes severe), blood in the urine, and infection. They are treated with medication and by drinking lots of fluids (or getting them through a needle in a vein). Sometimes urinary stones have to be removed by surgery.

Risk factors for bladder cancer

A risk factor is something, like a behavior, substance, or condition that increases your risk for developing cancer. Most cancers are caused by many risk factors. Smoking is the biggest risk factor for bladder cancer.

The risk of one day developing bladder cancer increases with age. This type of cancer usually shows up in people over the age of 65. Bladder cancer is more common in whites, and men have it more often than women.

Risk factors are usually ranked from most important to least important. But in most cases, it is impossible to rank them with absolute certainty.

| Known risk factors | Possible risk factors |

|

|

Researchers have looked into alcohol, artificial sweeteners, coffee and tea. They have found that there is no link between these factors and a higher risk for bladder cancer.

Researchers studied alcohol, artificial sweeteners, coffee and tea. They found that there was no link between these factors and an increased risk of bladder cancer.

Known risk factors

There is convincing evidence that the following factors increase your risk for bladder cancer.

Smoking

Smoking tobacco causes most bladder cancer. Cigarette smoking is most strongly associated with it, but cigars and pipes also increase the risk of bladder cancer.

The risk of bladder cancer is related to the number of tobacco products smoked each day, the number of years you smoked and how old you were when you started smoking. Smokers and former smokers are much more likely to get bladder cancer than people who have never smoked.

Arsenic

Arsenic is a substance found in nature. Drinking water can be contaminated with a high concentration of arsenic, which increases the risk of bladder cancer. Arsenic can come from natural sources, such as rock and soil, or from certain types of mining, smelting or manufacturing plants.

Occupational exposure to chemicals

People who work in the following industries are at greater risk of developing bladder cancer:

- professional painting

- rubber manufacturing

- aluminum and metal production

- manufacture of textiles and dyes

- transport

This increased risk is related to exposure to certain chemicals. Your risk is especially high if you are exposed to aromatic amines, including 2-naphthylamine, benzidine, 4-aminobiphenyl, and o-toluidine. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and fuchsin production also increases the risk of bladder cancer.

Diesel engine exhaust has also been identified as a probable cause of bladder cancer, but the link is not as strong as for the chemicals listed above.

Smokers exposed to these chemicals at work are even more likely to develop bladder cancer.

Cyclophosphamide

People who have been treated with the chemotherapy drug called cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Procytox) are more likely to have an irritated bladder, which makes it more likely that bladder cancer will develop.

To help protect the bladder, it is important to drink plenty of fluids when being treated with cyclophosphamide. Doctors sometimes give other medicines to help protect the bladder from irritation.

Radiation exposure

A person who has received radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvis is at greater risk of developing bladder cancer. A person who is exposed to radiation at work or who has survived an atomic bomb or a nuclear accident is also at higher risk of developing bladder cancer.

Chronic bladder irritation

If your bladder is irritated often, or if the irritation lasts for a long time, you are more likely to get bladder cancer. Irritation of the bladder can be caused by inflammation or injury.

Inflammation can be caused by bladder stones or chronic bladder infections. Schistosoma haematobium (S. haematobium) is a parasitic worm that infects the bladder and causes inflammation, called schistosomiasis, or bilharzia. This type of bladder infection occurs most often in developing countries. Chronic infection with S. haematobium increases the risk of bladder cancer.

The bladder injury can be caused by a catheter that stays in place for a long time, which some people need to help them empty their bladder.

Personal history of urinary tract cancer

Having cancer of any part of the urinary tract increases the risk of another tumor developing in the urinary tract, including the bladder.

Birth defects of the bladder

Urachal abnormality and exstrophy are rare birth defects that increase the risk of bladder cancer.

The urachus connects the navel to the bladder. It appears in the fetus and remains as a thin cord of fibrous tissue in adults. The urachis can become cancerous if a cyst forms along the cord or if it remains partially open.

Exstrophy occurs when the skin, muscle, and connective tissue in front of the bladder do not fully close during development, leaving an opening in the bladder wall. The inside of the bladder is therefore at risk of being exposed to microorganisms. This exposure can lead to chronic infections, which increase the risk of bladder cancer. The doctors treat estrophy as soon as they catch it, but people born with this birth defect are more likely to one day develop bladder cancer.

Possible risk factors

The following factors have been linked to bladder cancer, but there is not enough evidence to say that they are known risk factors. More research is needed to clarify the role of these factors in the development of bladder cancer.

Aristolochic acids

Studies show that aristolochic acids are present in certain types of plants. They may increase the risk of developing urothelial carcinoma in the ureters and pelvis of the kidney. You can be exposed to these acids if you eat or drink herbal products containing the aristochia species, whether in the form of capsules, extracts, teas or dried herbs.

Chlorine by-products

People who drink water from a river, lake or reservoir that is treated with chlorine for most of their lives may be at a slightly higher risk of developing cancer. of the bladder. When chlorine is used to disinfect water and make it drinkable, it breaks down into different chemicals called chlorine by-products. Chlorine byproducts that may increase the risk of bladder cancer are called trihalomethanes (THMs). Research is currently looking at other chlorine byproducts that may also increase the risk of bladder cancer.

Hairdresser profession

Studies suggest that hairdressers may be at higher risk of developing bladder cancer. Researchers believe this risk is related to exposure to hair dyes. Most of the evidence for this increase comes from studies of hairdressers prior to 1980. Subsequently, chemicals that could cause cancer were banned from hair dyes.

Family history

A family history of bladder cancer may increase your risk of developing this type of cancer. Researchers do not know whether certain genes or other factors that are passed from parents to children make families more likely to get bladder cancer when they are exposed to risk factors for bladder cancer.

Outdoor air pollution

Several studies show that outdoor air pollution can increase the risk of bladder cancer. Chemicals in the air that may increase this risk include arsenic and aromatic amines, among others.

Pesticides

Some studies with farmers show that the following pesticides can increase the risk of bladder cancer:

- chlorophenoxy

- organochlorine pesticides

- imazethapyr

- imazaquin

Some drugs

Phenacetin is a medicine used to relieve pain. When taken in large doses over a period of time, it can cause cancer of the ureters and pelvis of the kidney. This is why it has not been available in Canada since 1973. A number of studies show a link between excessive use of phenacetin and an increased risk of bladder cancer, but others have found that this risk was only linked to cancers of the ureters and pelvis of the kidney.

Pioglitazone is a medicine used to treat diabetes. Studies show that it may increase the risk of bladder cancer, especially in people who take high doses for long periods of time.

Unknown risk factors

It is not yet clear whether the following factors are linked to bladder cancer. This may be because researchers are unable to definitively establish this link, or the studies have yielded different results. More studies are needed to find out if the following are risk factors for bladder cancer:

- not drinking enough fluids

- coloring her hair

- smoke opium

Symptoms of bladder cancer

Bladder cancer may not cause any signs or symptoms in the very early stages of the disease. Signs and symptoms often appear as the tumor grows or grows deeper into the wall of the bladder. Other medical conditions can cause the same symptoms as bladder cancer.

The most common sign of bladder cancer is blood in the urine (hematuria). This may change the color of the urine, which may turn orange, pink or red. Sometimes the amount of blood in the urine is so small that it cannot be seen with the naked eye and can only be seen under a microscope during a urinalysis.

Here are some other signs and symptoms of bladder cancer:

- need to urinate more often than usual (frequent urination)

- urgent need to urinate (urgent urination)

- burning or pain when urinating

- difficulty urinating or weak urine stream

- lower back or pelvic pain

Diagnosis of bladder cancer

Diagnosis is a process of identifying the cause of a health problem. The diagnostic process for bladder cancer usually begins with a visit to your family doctor. He will ask you about your symptoms and may do a physical exam. Based on this information, your doctor may refer you to a specialist or order tests to check for bladder cancer or other health problems.

The diagnostic process can seem long and overwhelming. It’s okay to worry, but try to remember that other medical conditions can cause bladder cancer-like symptoms. It is important that the healthcare team rule out any other possible cause of the condition before making a diagnosis of bladder cancer.

The following tests are usually used to rule out or diagnose bladder cancer. Many tests that can diagnose cancer are also used to determine how far the disease has spread (stage). Your doctor may also give you other tests to check your general health and to help plan your treatment.

Health history and physical examination

Your health history consists of a checkup of your symptoms, your risks, and any medical events and conditions you may have had in the past. Your doctor will ask you questions about your history:

- symptoms that suggest bladder cancer, such as blood in the urine

- general symptoms that may suggest cancer, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, and night sweats

- smoking

- working with chemicals, such as paint, rubber, metals, textiles and dyes

- radiotherapy to the pelvis

- long-term (chronic) bladder irritation

Your doctor may also ask you questions about your family history:

- bladder cancer

- other cancers of the urinary tract

- risk of bladder cancer

- The physical exam allows your doctor to look for any signs of bladder cancer. During the physical exam, your doctor may do a pelvic exam or digital rectal exam (DRE).

Urinalysis and other urine tests

A urinalysis involves examining your urine. It can find and measure substances in a urine sample, such as blood, bacteria and cells. This is often one of the first tests done to check for urine abnormalities and urinary tract problems.

The presence of blood in the urine (hematuria) may mean that there is bleeding in the urinary tract, which could be caused by cancer. The presence of nitrites in the urine may mean that you have a urinary tract infection (UTI), or just a urinary tract infection.

A urine culture is used to check if there are bacteria and other germs in a urine sample that could be causing an infection. In the lab, urine is put in a special substance in which germs can grow. After a few days, the sample is examined under a microscope to see if bacteria or other germs have appeared. A urine culture is done to check if an infection may be the cause of the symptoms.

Urine cytology examines cells in a urine sample or bladder washings (the bladder is rinsed with salt water during a cystoscopy to remove cells). Urine cytology can be tested for abnormal cells, including bladder cancer cells.

Cystoscopy

A cystoscopy uses a thin tube with a lumen and a lens at the end (cystoscope) to look inside the bladder and urethra. It can detect any tumor or anomaly. Samples can be taken by biopsy or by bladder washings (rinses with salt water) during a cystoscopy. A cystoscopy is usually done when there is blood or abnormal cells in the urine.

A fluorescence cystoscopy can be done as well as a usual cystoscopy. A dye (contrast medium) and a special blue light are used to help make cancer cells easier to see. The doctor injects the dye into the bladder and then uses the cystoscope to emit a blue light. Cancer cells that have absorbed the dye will glow under the blue light.

A ureteroscopy may be done if the doctor wishes to observe the upper parts of the urinary tract. It takes place like a cystoscopy, except that the doctor look at the ureters and pelvis of the kidney.

Biopsy

During the biopsy, the doctor removes tissues or cells from the body for analysis in the laboratory. The pathologist’s report confirms whether or not there are cancer cells in the sample. Usually, small tumors are removed and the bladder biopsy done during a cystoscopy.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURT) is the most common type of biopsy done to diagnose bladder cancer. This is surgery to remove the tumor and part of the muscles in the bladder wall that are nearby. TURN can show how far the cancer has invaded the bladder wall (depth of invasion). It is also used to treat early bladder cancer.

Complete blood count

The complete blood count (CBC) is used to assess the quantity and quality of white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets. It may be used to check for anemia caused by prolonged bleeding in the urinary tract. CBC can also reveal if there is an infection.

The CBC is usually done before starting any cancer treatment, which provides a baseline against which to compare the results of future CBCs.

Blood biochemical analyzes

A blood chemistry test measures the level of chemicals in the blood. It makes it possible to assess the quality of functioning of certain organs and also to detect anomalies. The following are blood chemistry tests that are used to determine the stage of bladder cancer.

Kidney function tests are used to check how well the kidneys are doing. High levels of certain chemicals could mean you have kidney problems or a blocked urinary tract.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) is an enzyme found throughout the body. The bone and liver cells contain the greatest amount. A high blood pressure level can mean that the cancer has spread to the bones or the liver.

Liver function tests (including BP) are used to check how well the liver is doing. High levels of certain chemicals could mean that the cancer has spread to the liver.

Intravenous urography

Intravenous urography (IVU) is also called intravenous pyelography (IVP). It produces images of the urinary system, which includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. A dye is injected into a vein and it concentrates in the urine. X-rays are taken while urine is passing (with the dye) through the urinary tract. These images can help diagnose tumors and other abnormalities in the bladder and the rest of the urinary tract.

Ascending pyelography looks like IVU, but the dye is injected directly into the urinary tract, rather than into a vein, through a tube inserted into the urethra, during a cystoscopy. This procedure is sometimes used to find out what is blocking the normal flow of urine. It can also help diagnose cancer of the inner lining of the ureter or kidney. An ascending pyelogram may be done on a person who cannot pass IVU.

CT scan

A computed tomography (CT) scan uses special x-ray machines to produce 3-dimensional and cross-sectional images of the body’s organs, tissues, bones and blood vessels. A computer assembles the photos into detailed images.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is done to check for tumors or blockages in the urinary tract. It is also used to check if bladder cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, liver, or other organs and tissues around the bladder. A chest CT may be done to check if the bladder cancer has spread to the lungs.

Computed tomography urography, or uro-CT, is intravenous urography in which CT is used rather than the usual x-ray to produce images of the urinary tract. It checks for the presence of tumors in the urinary tract.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses powerful magnetic forces and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of the organs, tissues, bones and blood vessels of the horn.

Bladder cancer grades

The grade, or histological classification, defines how cancerous cells look when compared to normal, healthy cells. Knowing the grade gives your healthcare team an idea of how quickly cancer can grow and how likely it is to spread. It helps him plan your treatment. The grade can also help the healthcare team determine the possible outcome of the disease (prognosis), including how the cancer might respond to treatment and the likelihood that it will come back (come back).

To establish the grade of bladder cancer, the pathologist examines a sample of tissue taken from the tumor under a microscope. It checks how much cancer cells differ from normal cells (differentiation) and from other characteristics of the tumor such as the size and shape of cells and their arrangement. He can usually tell how fast the tumor is growing by looking at the number of dividing cells.

The pathologist can assign a grade of 1 to 3 for bladder cancer. The lower this number, the lower the rank.

Low-grade cancers are made up of well-differentiated cancer cells. These cells are abnormal, but they look a lot like normal cells and are arranged very similarly to normal cells. Low-grade cancers tend to grow slowly and are less likely to spread.

High-grade cancers are made up of poorly differentiated or undifferentiated cancer cells. These cells do not look like normal cells and are arranged very differently. High grade cancers tend to grow quickly and are more likely to spread than low grade cancers. They are also more likely to reappear after treatment. Almost all invasive bladder cancers are high grade when diagnosed.

Stages of bladder cancer

Staging describes or categorizes cancer based on how much cancer is in the body and where it was initially diagnosed. This is often referred to as the extent of cancer. Information from tests is used to find out how big the tumor is, what parts of the organ have cancer, if the cancer has spread from where it started and where it has spread. Your healthcare team uses the stage to plan your treatment and predict the outcome (your prognosis).

The most frequently used staging system for bladder cancer is the TNM classification. In the case of bladder cancer, there are 5 stages, ie stage 0 followed by stages 1 to 4. For stages 1 to 4, the Roman numerals I, II, III and IV are often used. But in order to make the text clearer, we will use the Arabic numerals 1, 2, 3 and 4. In general, the higher the number, the more cancer has spread. Talk to your doctor if you have any questions about the stage.

When doctors describe the stage, they can use the words local, regional, or distant. Local means the cancer is only in the bladder and has not spread to other parts of the body. Regional means near or around the bladder. Distant means in a part of the body farther from the bladder.

Find out more about the stage of cancer.

Stage 0

The tumor is found only in the lining of the bladder. Stage 0 includes these:

Stage 0A cancer is also called non-invasive papillary carcinoma. The tumor looks like a fungus.

Stage 0is cancer is called carcinoma in situ. The tumor is flat.

Stage 1

The tumor has grown into the connective tissue layer of the bladder.

Stage 2

The tumor has grown into the muscle layer of the bladder.

Stage 3A

The tumor has grown to nearby tissue outside the bladder but not the pelvic wall or abdominal wall.

OR

The cancer has spread to 1 lymph node in the pelvis.

Stage 3B

The cancer has spread to at least 2 lymph nodes in the pelvis or to at least 1 common iliac lymph node located just above the pelvis.

Stage 4A

The tumor has grown into the pelvic wall or the abdominal wall.

OR

The cancer has spread to lymph nodes farther from the bladder.

Stage 4B

The cancer has spread to other parts of the body (distant metastasis), such as to the lungs, liver or bones. It is also called metastatic bladder cancer.

Recurrence of bladder cancer

If bladder cancer comes back, the cancer comes back after treatment. If it reappears where it first started, it is called a local recurrence. If it reappears in tissues or lymph nodes near where it first started, it is called a regional recurrence. It can also reappear in another part of the body: this is called a recurrence or distant metastasis.

If bladder cancer spreads

Cancer cells can spread from the bladder to other parts of the body and form a new tumor. This new tumor is called a metastasis or secondary tumor.

Understanding how a type of cancer usually grows and spreads helps your healthcare team plan your treatment and future care. If bladder cancer spreads, it is more likely to spread to the following parts of the body:

- lymph nodes

- prostate

- vagina

- uterus

- rectum

- wall of the abdomen or pelvis

- lung

- bone

- liver

Prognosis and survival for bladder cancer

If you have bladder cancer, you may be wondering about your prognosis. A prognosis is the act by which the doctor best assesses how cancer will affect a person and how they will respond to treatment. The prognosis and survival depend on many factors. Only a doctor who is familiar with your medical history, the type of cancer you have, the stage and other characteristics of the disease, the treatments chosen and the response to treatment can review all of this data together with survival statistics. to arrive at a prognosis.

A prognostic factor is an aspect of the cancer or a characteristic of the person, such as their age and whether they smoke, that the doctor takes into account when making a prognosis. A predictor factor influences how cancer responds to a certain treatment. We often discuss prognostic and predictive factors together. They both play a role in choosing the treatment plan and in establishing the prognosis.

The following are the prognostic or predictive factors for bladder cancer.

Tumor depth and stage

The depth to which the tumor has invaded the wall of the bladder is an important prognostic factor. The deeper the tumor has invaded the bladder wall, the less favorable the prognosis.

Advanced bladder cancer that has spread beyond this organ to lymph nodes or other parts of the body has a poorer prognosis than early stage cancer.

Grade

Low-grade bladder cancer usually does not invade the muscle layer of the bladder wall and usually does not spread to other parts of the body. This is why low grade bladder cancer tends to have a good prognosis. High-grade bladder cancer is more likely to spread and have a poorer prognosis.

Tumors that are found only on the surface of the inner lining of the bladder (superficial tumors) are usually well differentiated. This means that the cancer cells look a lot like normal bladder cells. These tumors have a good prognosis.

Carcinoma in situ (CIS)

The presence of carcinoma in situ (CIS) in the bladder is associated with a less favorable prognosis. It is more likely to come back (recur) after treatment. The likelihood of it developing into invasive bladder cancer is also greater.

Tumor type

The prognosis differs for each type of bladder cancer. Papillary urothelial carcinoma has the best prognosis. Squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and small cell carcinoma tend to have a poor prognosis. They are usually invasive and diagnosed at a later stage.

Number of tumors

People with multiple tumors in the bladder or urinary tract are at greater risk of the cancer coming back (coming back) than people with only one tumor. The more tumors or areas affected by cancer, the less favorable the prognosis.

Tumor size

A small tumor has a better prognosis than a large tumor.

Recidivism

Bladder cancer that comes back after treatment (comes back) has a poorer prognosis than bladder cancer that appears for the first time (primary tumor). The more recurrences there are, the poorer the prognosis.

Non-invasive bladder cancer that comes back soon (a few months) after treatment is finished tends to have a less favorable prognosis than cancer that comes back long after treatment (years later).

Lymph or blood vessels affected by cancer

If the bladder cancer has spread to small lymphatic or blood vessels (lymphovascular invasion or ELV) or lymph nodes surrounding the bladder, the prognosis is poorer. These cancers are much more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Risk categories for early bladder cancer

Doctors classify cancers of the bladder that have not invaded the muscular layer of the lining of this organ into risk categories based on several factors, including the size and grade of the cancer. Risk categories allow doctors to assess the risk of the cancer coming back (recurring), developing and spreading (progressing). Doctors also use it to help plan the best treatment.

Non-invasive and non-muscle-invasive bladder cancers are classified as low risk, medium risk, or high risk.

Low risk

Bladder cancer is at low risk when:

there is only one low-grade tumor that is 3 cm or less;

there is no carcinoma in situ (CIS).

Medium risk

Bladder cancer is at moderate risk when:

it reappears within the first year after treatment and is low-grade papillary carcinoma present only in the lining of the bladder (non-invasive papillary carcinoma);

there is only one low-grade tumor that is larger than 3 cm;

there are several low grade papillary carcinomas in the lining of the bladder;

there is a high-grade tumor that is 3 cm or less;

there is a low-grade tumor that has grown into the connective tissue layer of the bladder.

High risk

Bladder cancer is at high risk when:

there is a high-grade tumor that has invaded the connective tissue layer of the bladder;

it only reappears in the lining of the bladder and is a high grade papillary carcinoma;

there is a high-grade tumor that measures more than 3 cm or when there are several high-grade tumors;

there is carcinoma in situ (CIS);

there are several tumors that are larger than 3 cm and low grade papillary carcinomas;

it is high grade and immunotherapy with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) has not been effective;

it is a variant of urothelial carcinoma;

it has invaded the small lymphatic and blood vessels surrounding the bladder (lymphovascular invasion, or ELV);

it is high grade and has invaded the part of the urethra that passes through the prostate (prostatic urethra).

Treatments for bladder cancer

If you have bladder cancer, your healthcare team will make a treatment plan just for you. It will be based on your health and specific cancer information. When your healthcare team decides which treatments to offer you, they take the following into consideration:

- the stadium (stage)

- the rank (grade)

- the risk category

- your functional index

- other medical problems that affect you

- what you prefer or want

You will be offered one or more of the following treatments for bladder cancer:

Surgery

Surgery is one of the main treatments for most bladder cancers. It may be used first or after other treatments such as chemotherapy. Depending on the stage of the cancer, one or more of the following types of surgery may be performed.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURT) involves removing the tumor from the bladder through the urethra. This is the most common way to diagnose bladder cancer. TURN is also used to treat early stage bladder cancers, including those that are non-invasive or non-muscle invasive.

Cystectomy involves removing part or all of the bladder. It is often used for bladder cancer that has invaded the muscular layer of the lining of this organ, which is muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Pelvic lymph node dissection involves removing the lymph nodes in the pelvis. This is usually done during a cystectomy.

Urinary diversion is reconstructive surgery in which a new way is created for urine to pass through the body. This is done after the entire bladder has been removed, which is called a radical cystectomy.

Immunotherapy

To treat early bladder cancer, the immunotherapeutic drug can be inserted directly into the bladder (intravesical immunotherapy) after TURNT. The most commonly administered immunotherapeutic drug is Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG).

To treat advanced or metastatic bladder cancer, immunotherapy may be used when chemotherapy is not working. An immunotherapeutic drug called an immune checkpoint inhibitor is then given.

Find out more about immunotherapy.

Chemotherapy

To treat early-stage bladder cancer, chemotherapy drugs may be given directly into the bladder (intravesical chemotherapy) after TURNT. Chemotherapy can be used instead of BCG. The most commonly used chemotherapy drug is mitomycin (Mutamycin).

To treat advanced bladder cancer, systemic chemotherapy is usually given before or after a radical cystectomy. In some cases, systemic chemotherapy can be combined with radiation therapy (chemoradiotherapy) and given after TURNT. It is also used to help improve the survival and quality of life of people with metastatic bladder cancer. Most often, a combination of chemotherapy drugs that includes cisplatin is used. Find out more about chemotherapy.

Targeted treatment

Targeted therapy is sometimes used to treat bladder cancer with certain genetic mutations that does not respond to treatment. Targeted therapy uses drugs to target specific molecules, such as proteins, present on the surface or inside of cancer cells in order to stop the growth and spread of cancer while limiting damage to cells. normal.

Radiotherapy

External beam radiation therapy is sometimes used to treat bladder cancer. It can be given as part of chemoradiation therapy for cancer that has invaded the muscular layer of the bladder wall. Chemoradiation is given after TURN to avoid having to remove the bladder, which is a bladder-preserving approach. External beam radiation therapy may also be used only if surgery cannot be done (the cancer is said to be unresectable) or to control bladder bleeding.

If you cannot or do not want to be treated for cancer

You may want to consider care that aims to make you feel better without treating the cancer itself, perhaps because cancer treatments no longer work, or they are no longer likely to improve your condition, or cause them to work. secondary are difficult to tolerate. There may be other reasons why you cannot or do not want to be treated for cancer.

Talk to members of your healthcare team. They can help you choose advanced cancer care and treatment.

Monitoring

Post-treatment follow-up is an important component supportive of care for people with cancer. You will need to have regular follow-up visits, especially during the first 2 years after treatment. These visits allow the healthcare team to monitor your progress and to know how you are recovering from treatment.

Clinical tests

Ask your doctor if there are clinical trials underway in some countries for people with bladder cancer. Clinical trials aim to find new methods of preventing, detecting and treating cancer.

Follow-up after treatment for bladder cancer

Follow-up after treatment for bladder cancer is an important part of the care you receive. Specialists, such as a urologist and oncologist, and your family doctor often share this responsibility. Your healthcare team will talk to you to decide which follow-up meets your needs.

Don’t wait until your next scheduled appointment to report any new symptoms and any symptoms that don’t go away. Tell your healthcare team if you have:

- blood in the urine (hematuria);

- a need to urinate more often than usual (frequent urination);

- an urgent need to urinate (urgent urination);

- burning or pain when you urinate;

- difficulty urinating;

- pain in the lower back or pelvis;

- loss of appetite;

- weight loss.

The risk of bladder cancer coming back (coming back) is greatest within 2 years of treatment, so you will need close monitoring during this time.

Planning of follow-up visits

Follow-up visits for bladder cancer are usually scheduled every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually. Your doctor may want frequent follow-up visits for more than 2 years. It depends on factors such as the stage and risk category of the cancer and the treatments you have received.

Progress of follow-up visits

During a follow-up visit, your healthcare team will usually ask you questions about the side effects of treatment and your ability to cope. We can also learn about the symptoms you are experiencing.

Your doctor may do a physical exam including:

- a pelvic exam or digital rectal exam (DRE);

- feel the pelvis and groin to see if the lymph nodes are swollen;

- feel the abdomen to see if the liver is swollen.

Examinations are often ordered as part of the follow-up. Doctors could ask these:

- cystoscopy and urine cytology to check for cancer (if your bladder was not removed as part of the treatment)

blood tests to check your overall health and how well your kidneys are working - computed tomography (CT) urography, computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound to check for cancer in the pelvis and abdomen

- x-ray or CT scan of the chest to see if the cancer has spread to the lungs

- If your healthcare team finds out that the cancer has come back, they will talk to you to plan your treatment and care.

Supportive care for bladder cancer

Supportive care empowers people to overcome the physical, practical, emotional and spiritual barriers of bladder cancer. It is an important component of the care of people with this disease. There are many programs and services that meet the needs and improve the quality of life of these people and their loved ones, especially after treatment is over.

Recovering from bladder cancer and adjusting to life after treatment is different for everyone, depending on the stage of the cancer, the organs and tissues removed during surgery, the type of treatment, and many other factors. The end of cancer treatment can lead to mixed emotions. Even if treatment is finished, there may be other issues to work out, such as coping with long-term side effects. A person who has been treated for bladder cancer may be concerned about the following.

Self-esteem and body image

Self-esteem is how we feel about ourselves. Body image is how we perceive our own body. Bladder cancer and its treatments can affect a person’s self-esteem and body image. Often this is because cancer or treatments can cause changes in the body such as bladder problems or a urostomy. Some of these changes may be temporary. Others can last a long time or be permanent.

For many people, body image and how other people look is closely related to self-esteem and can be a source of real concern and significant distress. They may be angry or upset, afraid to go out, or uncomfortable around others, although the effects of treatment may not be visible.

Some women may feel something different about themselves and their body after a radical cystectomy, which includes removing the uterus. Changes in sexual function after surgery or radiation therapy can affect self-esteem.

Counseling and emotional support can help you cope with changes in body image and self-esteem.

Loss of bladder control

Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence) is the inability to control the flow of urine from the body. Some people lose control of their bladder after surgery or radiation therapy for bladder cancer.

There are many ways to manage and help people cope with the loss of bladder control, including protectants, dietary changes, exercise, medications, and surgery.

Living with an ostomy

After surgery to remove the entire bladder, called a radical cystectomy, many people will need a urostomy to allow urine to flow out of the body.

Living with a urostomy can lead to fear at first. It takes time and patience to learn how to take care of a urostomy. Specially trained healthcare professionals, called enterostomal therapists, show people how to take care of their stoma after surgery. They also offer support and advice to people who have been discharged from the hospital.

Support and information can be obtained from local and national ostomy groups and associations.

Sexuality

Some treatments for bladder cancer, including radical cystectomy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, can affect sexuality and sexual function. Sexual problems depend on the type of treatment and they affect men and women in different ways.

In men, treatments for bladder cancer can cause:

- dry orgasms, that is, without semen, after the prostate has been removed;

- erectile dysfunction, also called impotence.

In women, treatments for bladder cancer can cause:

- infertility after removing the uterus and ovaries;

- menopause caused by treatment, including vaginal dryness, after the ovaries were removed or treated with radiation therapy;

- difficult or painful sex if part of the vagina has been removed or if radiation therapy causes the vagina to narrow.

Counseling and education can improve sexuality and help people cope with these concerns. Supportive measures, such as lubricants for vaginal dryness and medications such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), help manage the menopause caused by treatment. There are several types of treatment for erectile dysfunction including pills and implants.

Fertility disorders

Fertility problems may develop after treatment for bladder cancer with radical cystectomy, radiation therapy or chemotherapy. These problems affect a woman’s ability to get pregnant or carry a pregnancy to term, or a man’s ability to make a woman pregnant.

If you are concerned about your fertility, talk to your doctor before treatment.

List of all Cancers

The word “cancer” is a generic term for a large group of diseases that can affect any part of the body. We also speak of malignant tumors or neoplasms. One of the hallmarks of cancer is the rapid multiplication of abnormal growing cells, which can invade nearby parts of the body and then migrate to other organs. This is called metastasis, which is the main cause of death from cancer. Types of cancer (in alphabetical order of the area concerned):

Information: Cleverly Smart is not a substitute for a doctor. Always consult a doctor to treat your health condition.

Sources: PinterPandai, American Cancer Society, Web MD, Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinic

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Photo explanations: Locations of urinary bladder in males (left) and females (right).